The Art of Acting

by Steve Wedan

All cultures I’m aware of have forms of theatre. They consist of music and dance, and typically are performed either in worship to one or more deities or exist in an awareness of them: a context of the supernatural.

It was the ancient Greeks who separated acting as an art separate from song and dance, though it was still dependent on them. In fact, music and dancing by Dionysian priests, the so-called Greek chorus, were used to express the thoughts and fears a playwright wanted the audience to have. Using modern terms, the chorus modeled the behavior the audience should have.

The original word for actor was hypokrite, which meant “answerer.” The chorus would express thoughts and fears, and the actors would respond. In Greek tragedy, it’s this simple separation of question from answer that provides the framework for drama.

Actors. Image courtesy of Kyle Head on Unsplash.

So, if the leader of the chorus, backed by other priests, addresses the audience, asking, for example, whether a man’s destiny depends upon his choices or his predetermined fate, the action of the play will show characters in conflict, as they attempt to answer the question.

The key term here is conflict, which is the centerpoint of drama. So, in a soaring play such as Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, we come to realize that this tragic hero is doomed by both fate and choice. In fact, the two are inseparable. This is echoed two thousand years later by theologians such as John Calvin.

How do the actors, the answerers, actually answer?

The brilliance of Western Theatre is that, while acting is an activity distinct from its music and dance roots, those roots are means by which actors communicate. Speech and movement are the building blocks of performance (at least the obvious ones), and their quality can be defined as how closely they adhere to the grace and beauty of the arts from which they spring.

I began acting when I was sixteen years old. Until then, I certainly was interested in knowledge for its own sake; I was a learner by nature. But I slaked my creative thirst through writing and drawing. My future, as well as I could foresee it, was to become a professional writer and artist. Because of my intense interest in the natural world, I saw myself as a writer and artist for magazines such as Field & Stream.

Getting cast in a silly play at my high school, a comedy called Sleep, Baby, Sleep, changed everything. Everything. I began auditioning for everything I could and landing most of the roles I sought in high school: Horner in Inherit the Wind, Banquo in Macbeth.

Macbeth. Image courtesy of Matt Riches on Unsplash.

In undergraduate school, I majored in Theatre, and in graduate school, I earned my Master of Fine Arts degree in Acting. I’ve had training with the Folger Theatre and the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

(Do you see what I mean when I say that everything changed?)

During those years and in the years since, I’ve refined my acting style -- unconsciously at first -- to include a certain refinement based on music and dance. What I mean to say is that my naturalistic acting style is influenced now by the refinement of ballet and an ear for harmony with other actors.

Dance. Image courtesy of Samantha Weisburg on Unsplash.

For me, that brings the art of acting full circle to a place of worship. By that, I don’t mean to say that the script must be religious, without any bad words, or that, like David, who danced at the return of the ark of the covenant, it necessarily centers on God himself.

Understand that I’m not disparaging Christian drama. I’m just saying that for me, the experience is simply the working out of my own expression of creativity, a divine gift if there ever was one. In it, I find a joy that writing and drawing approximate. Acting differs from them mainly by being done with someone else, usually, and in front of an audience or camera lens.

Movie Camera. Image courtesy of Denise Jans on Unsplash.

To me, that is a “form-fitting ephod,” a revealing garment, if you will, to use the biblical reference to David’s dance. What I’m revealing is certainly the shape and condition of my body, but also the sharpness of my thoughts and the depth of my feelings. And the ways I express that include every choice I make on a scale from the gesture of a brute to the upwelling of a tear.

One might ask how this description isn’t anything more than an elevated form of exhibitionism, and my response dives deeper into the nature of theatre.

Let’s leave film out of it, for now. For the sake of clarity, I’ll speak of live performance.

The reason theatre works is because of something the Greeks understood, although their knowledge of how it works differed from ours. They believed that a healthy mind and body were the result of balancing the four “humors,” blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. When one or more of these humors was over- or under-abundant, it led to disease. Catharsis was the process of purification, a rebalancing of these humors, especially by purging pity and fear. The performance of Greek tragedy was thus considered healthy: how can a person avoid pity and fear watching a man hasten his own destruction, the loss of his daughters, the death of his wife/mother, and the destruction of his eyes because of his overarching pride? Oedipus’s fall from king to blind wanderer is essentially a fall from life to death. And he brought it upon himself, simply because his pride led him to think he was the only one who could save his city.

Today, we call this process of catharsis empathy. And that’s the point of what I claim to be a holy endeavor.

The actor empathizes with an imaginary person called the character. In so doing, he creates that role, brings it to life. It works because the actor identifies with the playwright’s invented person. It’s a shared humanity.

Empathy. Photo by Ricardo Gomez Angel on Unsplash.

The audience empathizes with the character the actor has created. It’s how story works: I watch someone going through an experience, and I invest myself -- my thoughts and my feelings -- in that imaginary person.

It’s because of empathy that a play can exist. It exists not on the stage. That’s just where the actor is playing his role; the onstage act is a symbolic, creative thing, not meant to be mistaken for reality. The play exists in the spaces between the stage and the audience. It exists in the shared, imaginative experience being danced and sung, to use the metaphor I cited above.

It’s a community-based experience. And when the audience member leaves her seat and drives home, it doesn’t exist anymore in experience. It only exists in memory.

Theater. Image courtesy of Peter Lewicki on Unsplash.

So, here we are with a titanically powerful thing that is brought to life only by the cooperation of everybody present and only in a place of precious empathy. Oedipus doesn’t suffer alone. We all fall from that high place and mourn the leaving behind of our children.

Loving the LORD with all my heart, soul, and mind, and loving my neighbor as myself requires an investment of my heart that is not unlike playing a role, any role almost, in such a way that it becomes an invitation to the audience to join in a kind of communion.

Doing so is not without cost. It’s a principle I find is lost in many modern churches. Getting all act-y makes adults squirm. They’d rather stand around and chat with cups of bad church coffee in one hand, the other hand jingling coins in their pocket, than do the hard work of preparing a play that, even absent any message the script has, is a holy undertaking requiring investment, if not sacrifice. Learning lines is only the beginning: That’s the tithe, the first ten percent. The rest of it is creating an environment, an altar, if you will, on which we build an imaginary world where the very ability to speak is itself a song and the very ability to move and gesture and make eye contact with the other actor is itself a dance.

To quote TS Eliot, it is “a condition of complete simplicity, costing not less than everything.”

The words of the song, of course, are important. As an actor with roughly a hundred plays performed, along with several dozen films and television shows, though, I will say this.

Go, find your words, your Christian plays.

But I’d also invite you to join me as I “sing” my lines and “dance” my gestures. The act of creativity itself, that flow, is my worship.

Because if you believe that the Creator gave the gift of creativity to the created, that can be its own praise and worship.

Detective Latta (Steve Wedan) in Howard's Mill (2017). Image courtesy of Steve Wedan.

Steve as Shawn’s Father from I, Tonya (2017). Image courtesy of Steve Wedan.

Timmy (Steve Wedan) from The Subject was Roses (1980). Image courtesy of Albert Wehlburg.

Headshot of Steve Wedan (2016). Image courtesy of Brent Harrington.

Mr. Penny (Steve Wedan) from Birds (2019). Image courtesy of Steve Wedan.

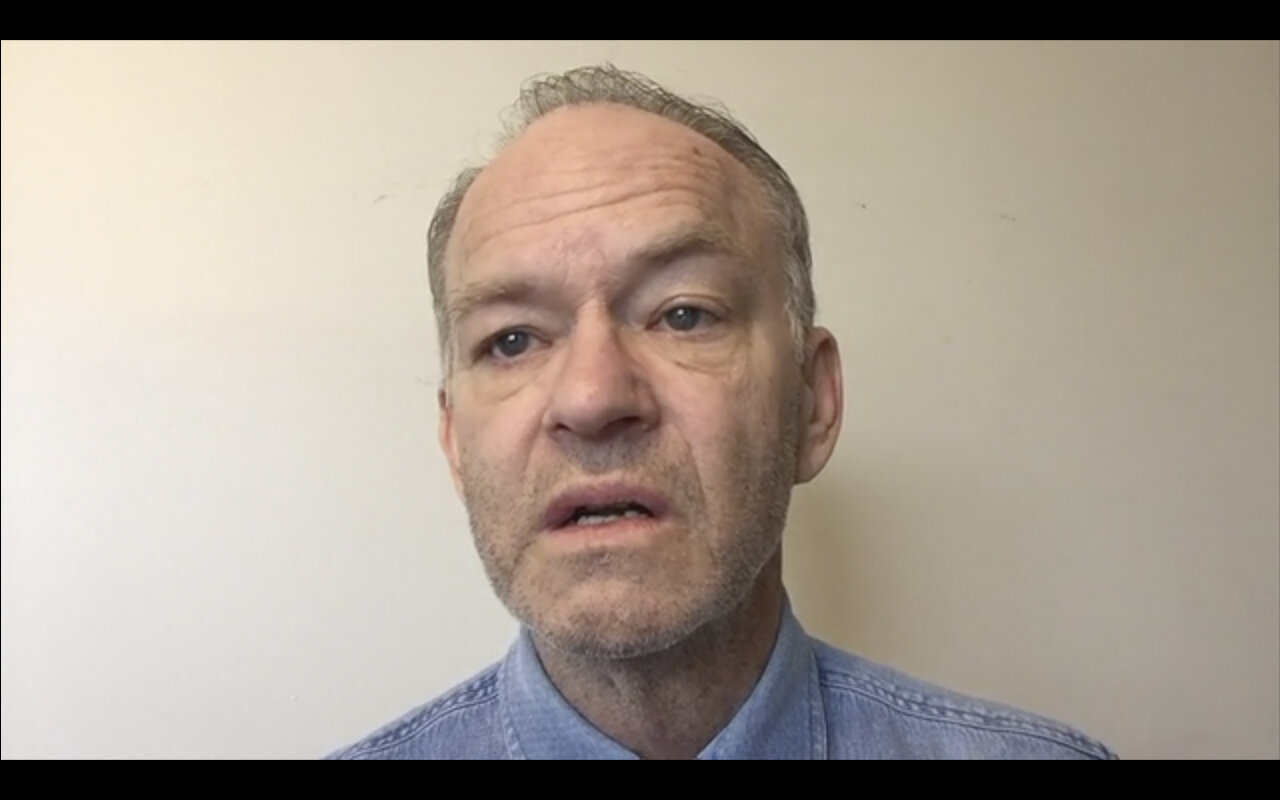

Steve auditioning for ManMan. (2020). Image courtesy of Steve Wedan.

Steve audition still for The Good Lord Bird (2019). Image courtesy of Steve Wedan.

Steve audition still for Mind Hunter (2018). Image courtesy of Steve Wedan.

Cardinal of New York (Steve Wedan) from Messiah (2020). Image courtesy of Steve Wedan.

Resources

We’ve created a free downloadable PDF to explore the article deeper. It contains discussion questions about the topic in general terms that will give you a jumping-off point for beginning a conversation.

The second page contains a way to see the topic from a biblical perspective.

And finally, to go deeper into the subject, we have chosen a few curated resources to explore from other authors’ and thinkers’ research or perspectives.

Read. Engage. Enjoy!

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Depending on how a gem is held, light refracts differently. At B+PC we engage in Pop Culture topics to see ideas from a new angle, to bring us to a deeper understanding. And like Pastor Shane Willard notes, we want “…Jesus to get bigger, the cross to get clearer, the Resurrection to be central…” Instead of approaching a topic from “I don’t want to be wrong,“ we strive for the alternative “I want to expand my perspective.”

So, we invite you to engage with us here. What piqued your curiosity to dig deeper? What line inspired you to action? What idea made you ask, “Hmmm?” Let’s join with our community to wrestle with our thoughts in love in the Comment Section! See you there!